Elastic object that stores mechanical energy

Helical coil springs designed for tension

Helical coil springs designed for tension

A heavy-duty coil spring designed for compression and tension

A heavy-duty coil spring designed for compression and tension

The English longbow – a simple but very powerful spring made of yew, measuring 2 m (6 ft 7 in) long, with a 470 N (105 lbf) draw weight, with each limb functionally a cantilever spring.

The English longbow – a simple but very powerful spring made of yew, measuring 2 m (6 ft 7 in) long, with a 470 N (105 lbf) draw weight, with each limb functionally a cantilever spring.

Force (F) vs extension (s).[citation needed] Spring characteristics: (1) progressive, (2) linear, (3) degressive, (4) almost constant, (5) progressive with knee

Force (F) vs extension (s).[citation needed] Spring characteristics: (1) progressive, (2) linear, (3) degressive, (4) almost constant, (5) progressive with knee

A machined spring incorporates several features into one piece of bar stock

A machined spring incorporates several features into one piece of bar stock

Military booby trap firing device from USSR (normally connected to a tripwire) showing spring-loaded firing pin

Military booby trap firing device from USSR (normally connected to a tripwire) showing spring-loaded firing pin

A spring is a device consisting of an elastic but largely rigid material (typically metal) bent or molded into a form (especially a coil) that can return into shape after being compressed or extended.[1] Springs can store energy when compressed. In everyday use, the term most often refers to coil springs, but there are many different spring designs. Modern springs are typically manufactured from spring steel. An example of a non-metallic spring is the bow, made traditionally of flexible yew wood, which when drawn stores energy to propel an arrow.

When a conventional spring, without stiffness variability features, is compressed or stretched from its resting position, it exerts an opposing force approximately proportional to its change in length (this approximation breaks down for larger deflections). The rate or spring constant of a spring is the change in the force it exerts, divided by the change in deflection of the spring. That is, it is the gradient of the force versus deflection curve. An extension or compression spring's rate is expressed in units of force divided by distance, for example or N/m or lbf/in. A torsion spring is a spring that works by twisting; when it is twisted about its axis by an angle, it produces a torque proportional to the angle. A torsion spring's rate is in units of torque divided by angle, such as N·m/rad or ft·lbf/degree. The inverse of spring rate is compliance, that is: if a spring has a rate of 10 N/mm, it has a compliance of 0.1 mm/N. The stiffness (or rate) of springs in parallel is additive, as is the compliance of springs in series.

Springs are made from a variety of elastic materials, the most common being spring steel. Small springs can be wound from pre-hardened stock, while larger ones are made from annealed steel and hardened after manufacture. Some non-ferrous metals are also used, including phosphor bronze and titanium for parts requiring corrosion resistance, and low-resistance beryllium copper for springs carrying electric current.

History

[edit]

Simple non-coiled springs have been used throughout human history, e.g. the bow (and arrow). In the Bronze Age more sophisticated spring devices were used, as shown by the spread of tweezers in many cultures. Ctesibius of Alexandria developed a method for making springs out of an alloy of bronze with an increased proportion of tin, hardened by hammering after it was cast.

Coiled springs appeared early in the 15th century,[2] in door locks.[3] The first spring powered-clocks appeared in that century[3][4][5] and evolved into the first large watches by the 16th century.

In 1676 British physicist Robert Hooke postulated Hooke's law, which states that the force a spring exerts is proportional to its extension.

On March 8, 1850, John Evans, Founder of John Evans' Sons, Incorporated, opened his business in New Haven, Connecticut, manufacturing flat springs for carriages and other vehicles, as well as the machinery to manufacture the springs. Evans was a Welsh blacksmith and springmaker who emigrated to the United States in 1847, John Evans' Sons became "America's oldest springmaker" which continues to operate today.[6]

Types

[edit]

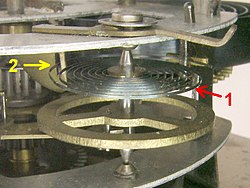

A spiral torsion spring, or hairspring, in an alarm clock.

A spiral torsion spring, or hairspring, in an alarm clock.

Battery contacts often have a variable spring

Battery contacts often have a variable spring

A volute spring. Under compression the coils slide over each other, so affording longer travel.

A volute spring. Under compression the coils slide over each other, so affording longer travel.

Vertical volute springs of Stuart tank

Vertical volute springs of Stuart tank

Selection of various arc springs and arc spring systems (systems consisting of inner and outer arc springs).

Selection of various arc springs and arc spring systems (systems consisting of inner and outer arc springs).

Tension springs in a folded line reverberation device.

Tension springs in a folded line reverberation device.

A torsion bar twisted under load

A torsion bar twisted under load

Leaf spring on a truck

Leaf spring on a truck

Classification

[edit]

Springs can be classified depending on how the load force is applied to them:

- Tension/extension spring

- The spring is designed to operate with a tension load, so the spring stretches as the load is applied to it.

- Compression spring

- Designed to operate with a compression load, so the spring gets shorter as the load is applied to it.

- Torsion spring

- Unlike the above types in which the load is an axial force, the load applied to a torsion spring is a torque or twisting force, and the end of the spring rotates through an angle as the load is applied.

- Constant spring

- Supported load remains the same throughout deflection cycle[7]

- Variable spring

- Resistance of the coil to load varies during compression[8]

- Variable stiffness spring

- Resistance of the coil to load can be dynamically varied for example by the control system, some types of these springs also vary their length thereby providing actuation capability as well [9]

They can also be classified based on their shape:

- Flat spring

- Made of a flat spring steel.

- Machined spring

- Manufactured by machining bar stock with a lathe and/or milling operation rather than a coiling operation. Since it is machined, the spring may incorporate features in addition to the elastic element. Machined springs can be made in the typical load cases of compression/extension, torsion, etc.

- Serpentine spring

- A zig-zag of thick wire, often used in modern upholstery/furniture.

- Garter spring

- A coiled steel spring that is connected at each end to create a circular shape.

Common types

[edit]

The most common types of spring are:

- Cantilever spring

- A flat spring fixed only at one end like a cantilever, while the free-hanging end takes the load.

- Coil spring

- Also known as a helical spring. A spring (made by winding a wire around a cylinder) is of two types:

- Tension or extension springs are designed to become longer under load. Their turns (loops) are normally touching in the unloaded position, and they have a hook, eye or some other means of attachment at each end.

- Compression springs are designed to become shorter when loaded. Their turns (loops) are not touching in the unloaded position, and they need no attachment points.

- Hollow tubing springs can be either extension springs or compression springs. Hollow tubing is filled with oil and the means of changing hydrostatic pressure inside the tubing such as a membrane or miniature piston etc. to harden or relax the spring, much like it happens with water pressure inside a garden hose. Alternatively tubing's cross-section is chosen of a shape that it changes its area when tubing is subjected to torsional deformation: change of the cross-section area translates into change of tubing's inside volume and the flow of oil in/out of the spring that can be controlled by valve thereby controlling stiffness. There are many other designs of springs of hollow tubing which can change stiffness with any desired frequency, change stiffness by a multiple or move like a linear actuator in addition to its spring qualities.

- Arc spring

- A pre-curved or arc-shaped helical compression spring, which is able to transmit a torque around an axis.

- Volute spring

- A compression coil spring in the form of a cone so that under compression the coils are not forced against each other, thus permitting longer travel.

- Balance spring

- Also known as a hairspring. A delicate spiral spring used in watches, galvanometers, and places where electricity must be carried to partially rotating devices such as steering wheels without hindering the rotation.

- Leaf spring

- A flat spring used in vehicle suspensions, electrical switches, and bows.

- V-spring

- Used in antique firearm mechanisms such as the wheellock, flintlock and percussion cap locks. Also door-lock spring, as used in antique door latch mechanisms.[10]

Other types

[edit]

Other types include:

- Belleville washer

- A disc shaped spring commonly used to apply tension to a bolt (and also in the initiation mechanism of pressure-activated landmines)

- Constant-force spring

- A tightly rolled ribbon that exerts a nearly constant force as it is unrolled

- Gas spring

- A volume of compressed gas.

- Ideal spring

- An idealised perfect spring with no weight, mass, damping losses, or limits, a concept used in physics. The force an ideal spring would exert is exactly proportional to its extension or compression.[11]

- Mainspring

- A spiral ribbon-shaped spring used as a power store of clockwork mechanisms: watches, clocks, music boxes, windup toys, and mechanically powered flashlights

- Negator spring

- A thin metal band slightly concave in cross-section. When coiled it adopts a flat cross-section but when unrolled it returns to its former curve, thus producing a constant force throughout the displacement and negating any tendency to re-wind. The most common application is the retracting steel tape rule.[12]

- Progressive rate coil springs

- A coil spring with a variable rate, usually achieved by having unequal distance between turns so that as the spring is compressed one or more coils rests against its neighbour.

- Rubber band

- A tension spring where energy is stored by stretching the material.

- Spring washer

- Used to apply a constant tensile force along the axis of a fastener.

- Torsion spring

- Any spring designed to be twisted rather than compressed or extended.[13] Used in torsion bar vehicle suspension systems.

- Wave spring

- various types of spring made compact by using waves to give a spring effect.

Main article: Wave spring

Physics

[edit]

Hooke's law

[edit]

Main article: Hooke's law

An ideal spring acts in accordance with Hooke's law, which states that the force with which the spring pushes back is linearly proportional to the distance from its equilibrium length:

,

,

where

is the displacement vector – the distance from its equilibrium length.

is the displacement vector – the distance from its equilibrium length. is the resulting force vector – the magnitude and direction of the restoring force the spring exerts

is the resulting force vector – the magnitude and direction of the restoring force the spring exerts is the rate, spring constant or force constant of the spring, a constant that depends on the spring's material and construction. The negative sign indicates that the force the spring exerts is in the opposite direction from its displacement

is the rate, spring constant or force constant of the spring, a constant that depends on the spring's material and construction. The negative sign indicates that the force the spring exerts is in the opposite direction from its displacement

Most real springs approximately follow Hooke's law if not stretched or compressed beyond their elastic limit.

Coil springs and other common springs typically obey Hooke's law. There are useful springs that don't: springs based on beam bending can for example produce forces that vary nonlinearly with displacement.

If made with constant pitch (wire thickness), conical springs have a variable rate. However, a conical spring can be made to have a constant rate by creating the spring with a variable pitch. A larger pitch in the larger-diameter coils and a smaller pitch in the smaller-diameter coils forces the spring to collapse or extend all the coils at the same rate when deformed.

Simple harmonic motion

[edit]

Main article: Harmonic oscillator

Since force is equal to mass, m, times acceleration, a, the force equation for a spring obeying Hooke's law looks like:

The displacement, x, as a function of time. The amount of time that passes between peaks is called the period.

The displacement, x, as a function of time. The amount of time that passes between peaks is called the period.

The mass of the spring is small in comparison to the mass of the attached mass and is ignored. Since acceleration is simply the second derivative of x with respect to time,

This is a second order linear differential equation for the displacement  as a function of time. Rearranging:

as a function of time. Rearranging:

the solution of which is the sum of a sine and cosine:

and

and  are arbitrary constants that may be found by considering the initial displacement and velocity of the mass. The graph of this function with

are arbitrary constants that may be found by considering the initial displacement and velocity of the mass. The graph of this function with  (zero initial position with some positive initial velocity) is displayed in the image on the right.

(zero initial position with some positive initial velocity) is displayed in the image on the right.

Energy dynamics

[edit]

In simple harmonic motion of a spring-mass system, energy will fluctuate between kinetic energy and potential energy, but the total energy of the system remains the same. A spring that obeys Hooke's law with spring constant k will have a total system energy E of:[14]

Here, A is the amplitude of the wave-like motion that is produced by the oscillating behavior of the spring.

The potential energy U of such a system can be determined through the spring constant k and its displacement x:[14]

The kinetic energy K of an object in simple harmonic motion can be found using the mass of the attached object m and the velocity at which the object oscillates v:[14]

Since there is no energy loss in such a system, energy is always conserved and thus:[14]

Frequency & period

[edit]

The angular frequency ω of an object in simple harmonic motion, given in radians per second, is found using the spring constant k and the mass of the oscillating object m[15]:

[14]

[14]

The period T, the amount of time for the spring-mass system to complete one full cycle, of such harmonic motion is given by:[16]

[14]

[14]

The frequency f, the number of oscillations per unit time, of something in simple harmonic motion is found by taking the inverse of the period:[14]

[14]

[14]

Theory

[edit]

In classical physics, a spring can be seen as a device that stores potential energy, specifically elastic potential energy, by straining the bonds between the atoms of an elastic material.

Hooke's law of elasticity states that the extension of an elastic rod (its distended length minus its relaxed length) is linearly proportional to its tension, the force used to stretch it. Similarly, the contraction (negative extension) is proportional to the compression (negative tension).

This law actually holds only approximately, and only when the deformation (extension or contraction) is small compared to the rod's overall length. For deformations beyond the elastic limit, atomic bonds get broken or rearranged, and a spring may snap, buckle, or permanently deform. Many materials have no clearly defined elastic limit, and Hooke's law can not be meaningfully applied to these materials. Moreover, for the superelastic materials, the linear relationship between force and displacement is appropriate only in the low-strain region.

Hooke's law is a mathematical consequence of the fact that the potential energy of the rod is a minimum when it has its relaxed length. Any smooth function of one variable approximates a quadratic function when examined near enough to its minimum point as can be seen by examining the Taylor series. Therefore, the force – which is the derivative of energy with respect to displacement – approximates a linear function.

The force of a fully compressed spring is:

where

- E – Young's modulus

- d – spring wire diameter

- L – free length of spring

- n – number of active windings

– Poisson ratio

– Poisson ratio- D – spring outer diameter.

Zero-length springs

[edit]

Simplified LaCoste suspension using a zero-length spring

Simplified LaCoste suspension using a zero-length spring

Spring length L vs force F graph of ordinary (+), zero-length (0) and negative-length (−) springs with the same minimum length L0 and spring constant

Spring length L vs force F graph of ordinary (+), zero-length (0) and negative-length (−) springs with the same minimum length L0 and spring constant

Zero-length spring is a term for a specially designed coil spring that would exert zero force if it had zero length. That is, in a line graph of the spring's force versus its length, the line passes through the origin. A real coil spring will not contract to zero length because at some point the coils touch each other. "Length" here is defined as the distance between the axes of the pivots at each end of the spring, regardless of any inelastic portion in-between.

Zero-length springs are made by manufacturing a coil spring with built-in tension (A twist is introduced into the wire as it is coiled during manufacture; this works because a coiled spring unwinds as it stretches), so if it could contract further, the equilibrium point of the spring, the point at which its restoring force is zero, occurs at a length of zero. In practice, the manufacture of springs is typically not accurate enough to produce springs with tension consistent enough for applications that use zero length springs, so they are made by combining a negative length spring, made with even more tension so its equilibrium point would be at a negative length, with a piece of inelastic material of the proper length so the zero force point would occur at zero length.

A zero-length spring can be attached to a mass on a hinged boom in such a way that the force on the mass is almost exactly balanced by the vertical component of the force from the spring, whatever the position of the boom. This creates a horizontal pendulum with very long oscillation period. Long-period pendulums enable seismometers to sense the slowest waves from earthquakes. The LaCoste suspension with zero-length springs is also used in gravimeters because it is very sensitive to changes in gravity. Springs for closing doors are often made to have roughly zero length, so that they exert force even when the door is almost closed, so they can hold it closed firmly.

Uses

[edit]

- Airsoft gun

- Aerospace

- Retractable ballpoint pens

- Buckling spring keyboards

- Clockwork clocks, watches, and other things

- Firearms

- Forward or aft spring, a method of mooring a vessel to a shore fixture

- Gravimeters

- Industrial Equipment

- Jewelry: Clasp mechanisms

- Most folding knives, and switchblades

- Lock mechanisms: Key-recognition and for coordinating the movements of various parts of the lock.

- Spring mattresses

- Medical Devices[17]

- Pogo Stick

- Pop-open devices: CD players, tape recorders, toasters, etc.

- Spring reverb

- Toys; the Slinky toy is just a spring

- Trampoline

- Upholstery coil springs

- Vehicle suspension, Leaf springs

See also

[edit]

- Shock absorber

- Slinky, helical spring toy

- Volute spring

References

[edit]

- ^

"spring". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) V. 25.

- ^ Springs How Products Are Made, 14 July 2007.

- ^ a b White, Lynn Jr. (1966). Medieval Technology and Social Change. New York: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 126–27. ISBN 0-19-500266-0.

- ^ Usher, Abbot Payson (1988). A History of Mechanical Inventions. Courier Dover. p. 305. ISBN 0-486-25593-X.

- ^ Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard (1998). History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Univ. of Chicago Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-226-15510-2.

- ^ Fawcett, W. Peyton (1983), History of the Spring Industry, Spring Manufacturers Institute, Inc., p. 28

- ^ Constant Springs Piping Technology and Products, (retrieved March 2012)

- ^ Variable Spring Supports Piping Technology and Products, (retrieved March 2012)

- ^ "Springs with dynamically variable stiffness and actuation capability". 3 November 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2018 – via google.com.

- ^ "Door Lock Springs". www.springmasters.com. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Edwards, Boyd F. (27 October 2017). The Ideal Spring and Simple Harmonic Motion (Video). Utah State University – via YouTube. Based on Cutnell, John D.; Johnson, Kenneth W.; Young, David; Stadler, Shane (2015). "10.1 The Ideal Spring and Simple Harmonic Motion". Physics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-48689-4. OCLC 892304999.

- ^ Samuel, Andrew; Weir, John (1999). Introduction to engineering design: modelling, synthesis and problem solving strategies (2 ed.). Oxford, England: Butterworth. p. 134. ISBN 0-7506-4282-3.

- ^ Goetsch, David L. (2005). Technical Drawing. Cengage Learning. ISBN 1-4018-5760-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "13.1: The motion of a spring-mass system". Physics LibreTexts. 17 September 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Harmonic motion". labman.phys.utk.edu. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "simple harmonic motion | Formula, Examples, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Compression Springs". Coil Springs Direct.

Further reading

[edit]

- Sclater, Neil. (2011). "Spring and screw devices and mechanisms." Mechanisms and Mechanical Devices Sourcebook. 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill. pp. 279–299. ISBN 9780071704427. Drawings and designs of various spring and screw mechanisms.

- Parmley, Robert. (2000). "Section 16: Springs." Illustrated Sourcebook of Mechanical Components. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0070486174 Drawings, designs and discussion of various springs and spring mechanisms.

- Warden, Tim. (2021). “Bundy 2 Alto Saxophone.” This saxophone is known for having the strongest tensioned needle springs in existence.

External links

[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spring (device).

- Paredes, Manuel (2013). "How to design springs". insa de toulouse. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- Wright, Douglas. "Introduction to Springs". Notes on Design and Analysis of Machine Elements. Department of Mechanical & Material Engineering, University of Western Australia. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- Silberstein, Dave (2002). "How to make springs". Bazillion. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- Springs with Dynamically Variable Stiffness (patent)

- Smart Springs and their Combinations (patent)

Machines

| |

| Classical simple machines |

- Inclined plane

- Lever

- Pulley

- Screw

- Wedge

- Wheel and axle

|

| Clocks |

- Atomic clock

- Chronometer

- Pendulum clock

- Quartz clock

|

| Compressors and pumps |

- Archimedes' screw

- Eductor-jet pump

- Hydraulic ram

- Pump

- Trompe

- Vacuum pump

|

| External combustion engines |

- Steam engine

- Stirling engine

|

| Internal combustion engines |

- Gas turbine

- Reciprocating engine

- Rotary engine

- Nutating disc engine

|

| Linkages |

- Pantograph

- Peaucellier-Lipkin

|

| Turbine |

- Gas turbine

- Jet engine

- Steam turbine

- Water turbine

- Wind generator

- Windmill

|

| Aerofoil |

- Sail

- Wing

- Rudder

- Flap

- Propeller

|

| Electronics |

- Vacuum tube

- Transistor

- Diode

- Resistor

- Capacitor

- Inductor

|

| Vehicles |

|

| Miscellaneous |

- Mecha

- Robot

- Agricultural

- Seed-counting machine

- Vending machine

- Wind tunnel

- Check weighing machines

- Riveting machines

|

| Springs |

|

Authority control databases  |

| International |

|

| National |

- Germany

- United States

- France

- BnF data

- Japan

- Israel

|